In an attempt to tackle adult obesity rates that now exceed 40% in the US, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) is advancing a proposed front-of-pack (FOP) labelling rule that would require most packaged foods to display whether a product contains low, medium or high levels of sugar, saturated fats and sodium.

But according to a new Georgetown University study, the FDA has failed to learn key lessons from other countries that have already tried similar approaches.

The study – authored by Hank Cardello, executive director of the Leadership Solutions for Health + Prosperity programme at Georgetown’s Business for Impact centre, and Dr Adam Drewnowski, director of the Center for Public Health Nutrition at the University of Washington – argues there is no hard evidence that interpretive warning labels improve consumer diets or curb obesity rates.

“I’ve said many times that food companies need to do much more to help people eat better and live healthier,” Cardello wrote in a Forbes article previewing the findings. “But this particular measure – to borrow from Chile – deserves a big black stop sign. Here is why.”

The study, sponsored by the Consumer Brands Association, analysed academic research, global obesity statistics and both short- and long-term data from dozens of countries where warning-style food labels are in place.

To unpack the debate, we examine how FOP labelling is being used across major markets, what the evidence shows so far, and why the Georgetown researchers are urging policymakers to rethink the strategy.

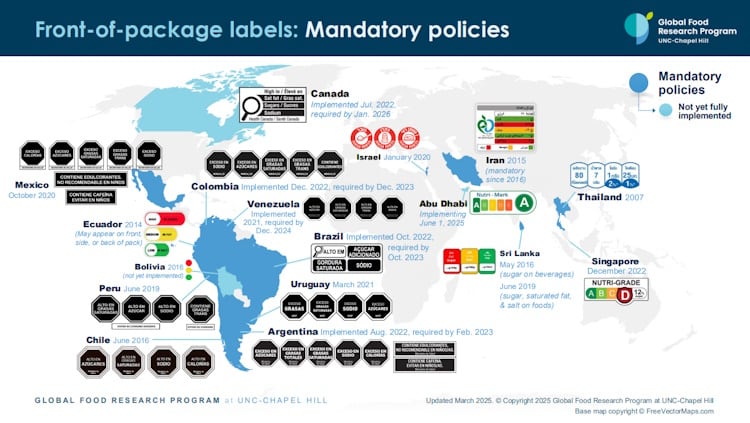

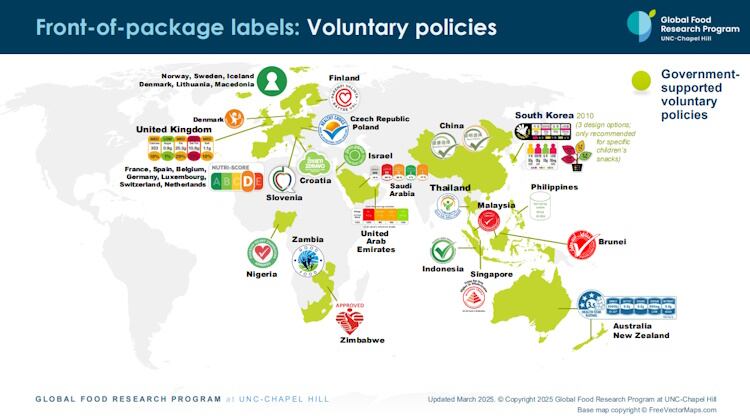

Global state of play

UK & EU: The UK still uses a voluntary traffic light system to indicate levels of fat, sugar and salt with red, amber and green symbols. In the EU, Nutri-Score – once seen as the frontrunner for a unified front-of-pack labelling system – has hit serious roadblocks. Although adopted by countries like France, Germany and Spain, Nutri-Score is now facing mounting opposition from several member states, food manufacturers and retailers. Critics argue its algorithm unfairly penalises traditional foods and doesn’t align with national dietary guidelines.

In March, FoodNavigator reported the European Commission may have effectively shelved plans to introduce a harmonised, mandatory FOP label across the EU, citing deep divides among member states and stakeholders. As it stands, Nutri-Score remains voluntary and nationally adopted, with no consensus on a bloc-wide standard in sight.

US: While the US currently mandates Nutrition Facts panels, front-of-pack labelling is not yet required. In January, the FDA introduced a proposed rule to require a standardised Nutrition Info box on most packaged foods. The label would highlight saturated fat, sodium and added sugars based on the percentage of Daily Value per serving. The black-and-white label would appear prominently on packaging and could also include voluntary calorie information.

If finalised, large manufacturers will have three years to comply and small manufacturers will have four. The public comment period is open until 16 May 2025. While the plan aims to simplify nutrition messaging, it has opened the door to even stricter measures – such as mandatory warning labels – prompting sharp debate among health advocates and industry groups alike.

Meanwhile, the longstanding voluntary Facts Up Front initiative – which is supported by the food industry – provides calorie and nutrient data on packaging but has been criticised for being interpretive-neutral and easy to overlook. It remains unclear whether this system will be phased out or adapted under future FDA regulations.

Additionally, the Guiding Stars programme, an interpretive labelling scheme used by several major US retailers, assigns 1-3 stars to foods based on a proprietary nutritional algorithm. Though helpful, its limited scope and proprietary nature have restricted broader regulatory impact.

Latin America: Chile and Mexico are among the global leaders in mandatory FOP warning labels. Chile’s black stop-sign warnings for products high in sugar, salt or fat led to a 36.8% drop in sugar consumption and a 23% drop in average calories purchased per transaction. Mexico’s similar octagonal label has been credited with improving consumer understanding and shifting purchasing behaviour.

Australia & New Zealand: These countries have implemented the Health Star Rating system, scoring foods from 0.5 to 5 stars. The voluntary programme has gained wide industry adoption and has reportedly encouraged modest product reformulation.

Scandinavia & Canada: The Scandinavian Keyhole system identifies healthier options within food categories and is widely recognised by consumers. Canada, meanwhile, has recently introduced mandatory FOP symbols for foods high in sodium, sugars or saturated fat. New rules, which went into effect in 2023, have already begun shifting industry reformulation efforts.

Why healthy shoppers ignore labels

Research suggests that interpretive food labels often resonate most with people who are already health-conscious - consumers who tend to seek out nutrition information and make informed choices regardless of labelling. As Cardello wrote in Forbes, FOP systems risk “preaching to the choir,” doing little to influence the dietary habits of those most at risk. For labels to be more effective, they must reach and motivate the least engaged consumers - those who typically overlook or disregard nutrition guidance altogether.

Effectiveness of FOP labels

Numerous studies suggest that FOP labels can influence consumer choice and encourage industry reformulation.

A 2023 study estimated that implementing FOP nutrition labelling could reduce obesity prevalence by approximately 0.32 percentage points, indicating a limited direct effect on obesity rates.

A 2020 meta-analysis of 14 experimental studies by the Global Food Research Program of the University of North Carolina found that ‘high in’ warning labels reduced calorie and sugar content in purchases. In Canada, proposed warning labels prompted reformulation and reduced consumer purchase of products high in saturated fat and sugar. In Chile, initial results after the implementation of FOP warnings showed significant reductions in consumption of sugar-sweetened beverages and packaged snacks.

However, the relationship between these behavioural changes and long-term health outcomes remains ambiguous. Despite reduced purchases of so-called ‘unhealthy foods’, obesity rates in Chile rose from 68% in 2010 to 79% in 2022. Similarly, studies in other regions show that while FOP labels are widely understood and accepted, their real-world impact on population health metrics like obesity and diabetes remains limited.

Georgetown University’s divergent view

The Georgetown study found that despite the popularity of FOP labelling, the strategy has largely failed to deliver on its promise. Key findings include:

Limited impact on obesity rates: Despite wide adoption of FOP systems in countries like Chile, Mexico and France, the study found little correlation between labelling efforts and obesity reductions.

Effectiveness varies by context: Labelling systems work differently depending on the population.

Systemic solutions needed: The authors argue that FOP labels are not a silver bullet and must be part of a broader mix of strategies, including sugar taxes, restrictions on marketing to children and better food access policies.

Minimal industry reformulation: While some manufacturers adjust products to improve label scores, these changes are often small and do not transform a product’s health impact.

Behavioural complexity: Taste, cost, convenience and marketing exert a much stronger influence over consumer food choices than labels.

The Georgetown study raises critical questions about the future of FOP regulations and their business implications. While FOP labels may encourage consumers to reach for better-rated options or prompt minor reformulation, this may not be enough to stave off stricter policies in the future.

The study suggests that brands looking to position themselves as health-conscious must go beyond labelling compliance. This means prioritising meaningful reformulation, transparent marketing and participation in broader public health initiatives.

With the FDA considering new FOP rules and debates escalating across the EU, UK and Australia, manufacturers should expect FOP standards to tighten in the coming years. While FOP labelling is here to stay, the Georgetown study provides a timely reminder that labels are not a panacea and that truly addressing obesity requires action on multiple fronts.

As public health agencies take stock of the past decade’s efforts, the next generation of policy may hinge on whether governments choose to double down on labels or build a more comprehensive strategy to reshape our food systems.

“Addressing the obesity crisis will require commitment, money and patience to see results,” Cardello penned in Forbes. “While transparency is necessary to inform consumers what they’re buying, the FDA must recognise that front-of-pack interpretive warning labels are not a magic bullet. Portion control must be part of the tool kit. Change won’t happen overnight - but neither did the ballooning portion sizes that got us here.”

Studies:

Can Front-of-Pack Product Labeling Fix the Obesity Crisis?

Authors: Hank Cardello, Dr Adam Drewnowski

Business for Impact at Georgetown University’s McDonough School of Business, April 2025

Authors: Natália Cristina de Faria, Gabriel Machado de Paula Andrade, et al

PLoS One. 2023 Aug 11;18(8):e0289340. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0289340

Authors: Anita Shrestha, Katherine Cullerton, et al

Appetite, Volume 187, 2023, 106587, doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2023.106587.

Authors: Lindsey Smith Taillie; Bercholz, Maxime Bercholz, et al

The Lancet. Planetary Health. 5 (8): e526-e533. doi:10.1016/S2542-5196(21)00172-8.