In 2016, Chile brought in a swathe of food regulations to curb rising childhood obesity. Measures included front-of-pack warning labels, marketing restrictions for under fourteens and a ban on foods high in salt, fat, and sugar in schools.

A study published this month found the regulations have made mothers more aware of the importance of eating healthily, made it easier to choose healthy processed foods and have even made children actors in their own food choices.

In a country where one-quarter of schoolchildren and almost one-third of Chiles’s adults are obese, the findings are “overwhelmingly positive”, said the researchers in a statement.

Lindsey Smith Taillie, assistant professor of nutrition at the UNC Gillings School and co-author said: “This study shows that regulations really change how mothers think about and purchase food for their children. Perhaps more importantly, children are key drivers in changing social norms and behaviors after the law."

Barry Popkin, professor of nutrition at the UNC Gillings School and senior investigator for the overall Chilean food law evaluation project, also noted the importance of the regulations.

"This study, and others that follow, suggest that this cluster of regulations represents the first potential set of policies that may change food norms and tackle the poor-quality diets that increasingly affect children globally," he said.

For this study, the scientists used qualitative data from nine focus groups carried out in 2017.

Each group contained up to 10 mothers, with the nine groups corresponding to three socio-economic classes (lower, middle and upper) and the ages of their children (2–6, 7–10 or 11–14).

The scientists chose to question mothers because, in Chile, it is usually women with children who buy the family's food. As such, they are “gatekeepers for food availability in the household” and, therefore, “key stakeholder of the new policy”.

“Understanding their perceptions is particularly relevant,” the scientist wrote.

We have listed the key findings below.

Warning labels were an eye-opener

Mothers described feeling “cheated” or "disappointed" and spoke of having their eyes opened when products they thought of as healthy, such as oatmeal cookies, breakfast cereal, and cereal bars, had warning labels.

Dominique, for instance, used to buy Nutrabien (‘Nutragood’) muffins for her five-year-old boy.

She said: “I [thought] the brand Nutrabien was very healthy until those black labels came out. I realized that it had high levels of everything, and I felt very cheated (…) I really had no idea, I never paid attention. Now, I do pay attention.”

Children have become ‘agents of change’

Young children are receptive to the highly mediatized messages on healthy eating and, because the warning labels are easy to understand, use the labels as shortcuts to categorize food as either healthy or unhealthy.

“As a result, [children] have become change agents in their families by forcing or persuading their mothers to change some food consumption habits,” wrote the researchers.

Soledad, a secretary, and mother of a six-year-old boy, said: “My son likes cookies a lot, so I tell him in the supermarket ‘look for the cookies that have the fewest labels and that one you can take. So, it is useful for me that he, by himself, realizes what is bad.

“He tells me, ‘Mom, look, this one has three (labels)’. [I say]: ‘No, too much. Look for another that has one.’”

The fact that healthy eating is incorporated into children’s school environment also increases its impact. Gina, a mother of a five-year-old, said: “Because of this new law, my daughter has taught [me] a lot about these black logos. ‘No mom, you can’t buy me that, my teacher won’t accept it because it has those labels’.”

Teresa Correa, lead author and associate professor at the Diego Portales University in Santiago said the study showed the importance of tackling obesity with a set of multi-faceted strategies. “We found that they reinforced each other,” she said.

Social norms are changing

Some mothers said there was a “clear social pressure” to give their children healthy food and they felt guilty when giving unhealthy snacks to their kids.

Mothers, particularly from the middle and upper class, said they felt pressure from the school –and society in general—about their children’s healthy eating.

“I feel [like] a terrible mom when I see her eating chips. I let her do it sometimes because at a party, I won’t say ‘don’t eat’ but I know it’s not good for her,” said one.

Some mothers, particularly those from lower socio-economic backgrounds, however, said the restrictions were unwarranted.

“Playground: healthy. Home: healthy. TV: healthy,” said Vania, mother of a five-year-old. "Sometimes it is good to spoil them. It is not like it’s going to happen every day. If almost everyone eats [junk food], why should we forbid them?”

Reformulation should be clearly communicated

In some cases, individuals were suspicious and skeptical when manufacturers reformulated to remove all warning labels – especially products on which they expected to see at least one.

The scientists wrote: “For instance, [when] a dairy brand advertised that all its products were free of labels, including caramel and chocolate-based puddings […] this elicited confusion and affected the credibility of FOP labels among a few participants.”

“I don’t even believe in light products, said one of the mothers, Paulette, a psychologist. “I think… ‘what are they putting [into the food]’ because now everything is processed, everything.”

Manufacturers could try to avoid this by communicating how they have made the product healthier, for instance by swapping sugar for stevia.

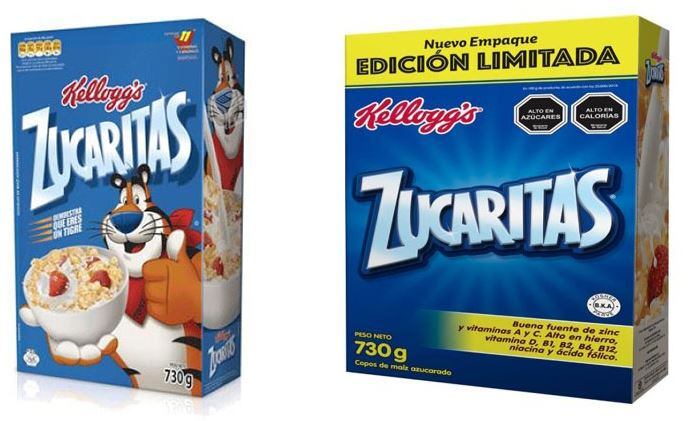

Tony the tiger hasn’t been missed (by mums)

The restrictions placed on marketing went mostly unnoticed by the mothers with only a few participants realizing products no longer included cartoons or animals, for instance.

According to the researchers, this was not surprising as marketing messages are often implicit. The fact they went unnoticed did not mean the restrictions have not had an impact on consumers’ behavior, they said.

Positive marketing labels may go unnoticed

Some food brands have tried to counteract the negative effect of having too many black labels by adding additional information, such as ‘Suggested portion = 3 cookies → 101 cal; 15 cookies → 3 logos’.

Most participants said they “barely noticed” these additional labels, wrote the researchers, while others thought they were part of the regulation. Other mothers spoke of label fatigue and thought the packs were cluttered.

Future research should focus on whether the warning labels’ impact is down to their novelty and if people could become desensitized in the long-run, the scientists write.

Source: International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity

Published online ahead of print, 13 February 2019, doi.org/10.1186/s12966-019-0781-x

“Responses to the Chilean law of food labeling and advertising: exploring knowledge, perceptions and behaviors of mothers of young children”

Authors: T. Correa, et al.